„In the very early days of the Christian era, long before England had assumed any importance, long even before her people had united into a nation, our ancestors had attained a great empire, which lasted until the eleventh century, when it fell before the attacks of the Moors of the North. At its height that empire stretched from Timbuktu to Bamako and even as far as to the Atlantic. It is said that lawyers and scholars were much respected in that empire and that the inhabitants of Ghana wore garments of wool, cotton, silk and velvet. There was trade in copper, gold and textile fabrics, and jewels and weapons of gold and silver were carried.“ (Autobiography) „By far the greatest wrong which the departing colonialists inflicted on us, and which we now continue to inflict on ourselves in our present state of disunity, was to leave us divided into economically unviable states which bear no possibility of real development…. We must unite for economic viability, first of all, and then to recover our mineral wealth in Southern Africa, so that our vast resources and capacity for development will bring prosperity for us and additional benefits for the rest of the world. That is why I have written elsewhere that the emancipation of Africa could be the emancipation of Man.“ (Speech OAU Summit Conference Cairo 7/19/64)

The roots of Ghanaian nationalism go back to the early decades of the 20th century. It owed much to the influences of the Pan- African Movement of Sylvester Williams, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Padmore and Marcus Garvey among others and the West African Students’ Union based in the United Kingdom. Dr. Du Bois’ first Pan- African Congress was held in Paris in 1919; and within a year of that meeting, Casely Hayford convened the inaugural meeting of the National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA) in Accra. The NCBWA was intended as a platform for the intelligentsia of British West Africa to bring “before the government the wants and aspirations of the people” for attention. In the longer term, the Congress aimed at the attainment of self-government for British West Africans by constitutional means. Among the specific demands of NCBWA were the election of African representation to both the Legislative and Municipal Councils; cessation of the exercise of judicial functions by untrained public servants; the opening up of the Civil Service to Africans; establishment of a British West African University and compulsory education. Following the death of Casely Hayford in 1930, the NCBWA became ineffective; and in the mid 1930ies, national politics became radicalized as a result of the activities of the Sierra Leonean, Isaac Wallace Johnson, and then based in the Gold Coast, and his West African Youth League. The colonial government and the chiefs, who were seen as their collaborators, came under increasing pressure as a result. Nationalist agitation was suspended during the Second World War years of 1939 to 1945 but was resumed after 1945. Indeed, the peoples of the Gold Coast actively supported the British war effort, contributing troops and funds to purchase a helicopter. The 5th Pan- African Congress held in Manchester in October 1945 inspired Dr. Nkrumah. He returned home at the invitation of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) which had been formed on 4 August 1947 to help free the Gold Coast from colonial rule “within the shortest possible time”. Dr. Nkrumah’s formal political activity started in America but only began in earnest in London, where he went for further studies in 1945. While in England, he edited a Pan- African journal, was vice president of the West African students‘ union, and helped organize the Fifth Pan- African Conference in Manchester. There, too, George Padmore, the important former communist and Pan- Africanist, became his mentor and was a crucial restraining influence until he died in 1959.

The Man Dr. Kwame Nkrumah

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, stands out not only among the Big Six but also among the greatest statesmen of history. It was he who canalized the discontent of the people of the Gold Coast Colony into the highly organized movement of protest against British rule, and within a relatively short period won political independence for Ghana on March 6, 1957. With Ghana independent, Nkrumah worked to liberate the whole of the African Continent. He supported and financed liberation struggles and nationalist movements throughout the continent. His efforts soon yielded dividends as the majority of countries on the continent gained independence. Then he turned his efforts to forging a common union of African states. This he believed was the key to giving a strong voice to the whole continent and pride of place to the Blackman. Indeed Dr. Nkrumah’s contributions are legion. Apart from being a brilliant leader of the ordinary people and a great champion of their cause, he is remembered as an outstanding statesman of Ghana and Africa who stands shoulder to shoulder with such great leaders of the twentieth century as V.I. Lenin of USSR, Mao Tse-tung (Zedong) of China, Fidel Castro of Cuba, J.F.K. Kennedy of USA and Winston Churchill of Great Britain.

His life

Kwame Nkrumah was born on September 21, 1909, at Nkroful in the Western Region. His father had many wives and children but he was his mother’s only child. Throughout his life his mother, Elizabeth Nyaniba, served as a tower of strength to him. „I never cared for any woman as much as I cared for her. We are both alike in one thing. We seem to draw strength from each other. In the same way I feel better for seeing her, she gets better if she is ill and I visit her“, Nkrumah wrote about his mother. When Nkrumah was about three years old, his mother brought him to Half Assini, where his father worked as a goldsmith. He began his schooling at the local Catholic School where he was also baptized and named Francis. The German Roman Catholic priest George Fischer influenced his elementary school education. On completing his course as a top student in his class, he was given a pupil-teaching appointment at a PrimarySchool in Half Assini. In 1926, the Rev. A.G. Fraser, an educationist, visited Nkrumah’s school. He was so impressed about Nkrumah’s output that he recommended he should go for further studies to the Accra Government Training College. At this College, Nkrumah came under the influence of Dr. Kwegyir Aggrey who helped him tremendously to come out of his depression and financial crisis which had been commissioned by the death of his father in that same year. When in 1928, the Accra Training College was moved to Achimota and made part of the Prince of Wales College, Nkrumah was enrolled and began working hard to catch up with his new mates; most of them had finished Secondary School. Among his favourite subjects were history and psychology. Outside the classroom, he was active in the Aggrey Students‘ Society (a debating society).

He was also very active in sports and ran for the College in the 100 and 200 yards dashes. He graduated from the College in 1930, and his career in teaching began at the Roman Catholic Junior School in Elmina. As a teacher, he was reckoned to have pedagogical gifts. Basil Davidson, a biographer of Nkrumah, quotes a former school inspector who once sat in a lesson given by the young Nkrumah to prove that point: “I have never forgotten our meeting since I was suddenly made aware that here was no ordinary teacher. Despite a frieze of noisy spectators at the open windows, the pupils reacted to his calm, dignified and ‘magnetic’ manner whole-heartedly. It was an unforgettable inspectorial experience.” While teaching at Elmina, Nkrumah used much of his spare time to help found the Teachers‘ Association. This Association aimed at improving the status of teachers, supplying them with the means of airing some of their grievances and getting them remedied by the authorities. After one year in Elmina, he was transferred to Axim and made the headmaster of the local Roman Catholic Junior School. While there, he took a private course to prepare himself for the University of London Matriculation. He, however, failed the Latin and Mathematics papers of that examination. In 1933, the Roman Catholic Mission in Gold Coast opened a seminary at Amissano near Elmina to train its priests. As one of the brilliant young teachers of the church, Nkrumah was invited to teach there. Amissano was to have considerable influence on him as he regained his religious fervour, which he had almost abandoned. He even formed the idea of joining the Jesuit Order and taking the vocation of priesthood. This idea lingered on in him for a whole year, but eventually it was replaced by the old desire of furthering his education. For the place to go overseas, Nkrumah chose the USA. He had around that period come into contact with the views of a foremost African nationalist, Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik), who was then editor of The African Morning Post. Zik’s ideas greatly influenced Nkrumah. So just like Azikiwe who schooled in the USA, (later Nigeria’s first president), Nkrumah saw the USA as an ideal place to go in order to get a first hand knowledge of liberty and equality. At the close of 1934, he applied for admission to Lincoln University, the first institution of higher learning for blacks. His passage money was provided by two relatives: the Chief of Nsuaem in the Wassa Fiase State (northwest of Tarkwa), and another who had moved to Lagos, Nigeria.

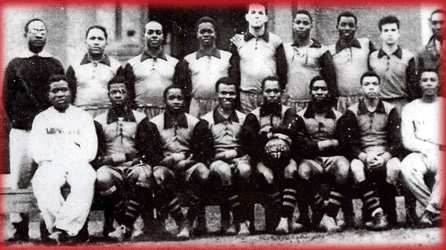

Standing: 1st from left Kwame Nkrumah; Sitting: 2nd from left Ebenezer Ako Adjei

Nkrumah arrived in New York towards the end of October 1934 and began his studies in Economics and Sociology at the Lincoln University. In 1939, he obtained his B.A. Degree with Major in Economics and Sociology, and in 1942 qualified as Bachelor of Theology. He proceeded to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia where he obtained a M.Sc. Degree in Education and an M.A. in Philosophy. While at the University of Pennsylvania, he helped to set up the African Studies section, there. He also helped to organize African students in America and Canada into an African Students’ Association of America and Canada. At the first congress of the Association, Dr. Nkrumah was elected its president. In the course of his organizational work, he met C.L.R. James, a historian of note from Trinidad, then living in the USA. Through James, he learned about political organizations and took deep interest in the writings of Marxists and other revolutionary philosophers. Dr. Nkrumah was particularly inspired by the thoughts of the Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey, the charismatic Jamaican who initiated a Back-to-Africa movement, and of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois who in his capacity as one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colour People was writing authoritatively on African Affaires. Through Marcus Garvey, Dr. Nkrumah decided to embark on a programme to systematically rid Africa of colonialism and neo-colonialism. We shall examine subsequently his contribution to the process of decolonialisation in Africa and its result. Dr. Nkrumah’s ultimate way to the presidency of Ghana was paved by his political activism in the United States and the U.K. He returned to the Gold Coast, as it was then called, on the 10th of December 1947, after a 12 years absence.

Gold Coast at this time was still under British imperial control and the pot was now brewing for political sovereignty, a demand that was influenced by the leftist Wallace Johnson. The colonial government deported Johnson in 1938 and suppressed other anti-colonial and anti-tax movements. Dr. Kwame Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast as tensions were escalating rapidly. In the same year 1947, the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) was established, and Dr. Nkrumah became its secretary and chief organizer. He transformed it from a grassroots movement into a political party. Dr. Nkrumah engaged in a series of discussions with the leadership (headed by Dr. Joseph B. Danquah and also called “The Big Six”) of the United Gold Coast Convention to clamour for constitutional reform. The stage had been set for political autonomy from Great Britain. This national movement was essentially middle-class in its origin and conservative in its policies.

The Big Six

They were:

- Dr. Kwame Nkrumah – later first prime minister and first president of Ghana

- Emmanuel Odarkwei Obetsebi-Lamptey – founding member of the UGCC

- Dr. Ebenezer Ako-Adjei – founding member of the UGCC

- Edward Akufo-Addo – founding member of the UGCC and later chief justice and then president of Ghana

- Dr. Joseph Boakye Danquah – founding member and head of the UGCC

- William Ofori Atta – founding member of the UGCC

One day after some disturbances, the UGCC leaders sent a cable to the Secretary of State in London: „…unless Colonial Government is changed and a new Government of the People and their Chiefs installed at the centre immediately, the conduct of masses now completely out of control with strikes threatened in police quarters, and rank and file police indifferent to orders of officers, will continue and result in worse violent and irresponsible acts by uncontrolled people…. Working Committee United Gold Coast Convention declares they are prepared and ready to take over interim government. We ask in the name of oppressed, inarticulate, misruled and misgoverned people and their Chiefs that a Special Commissioner be sent out immediately to hand over government to interim Government of Chief and People and to witness immediate calling of Constituent Assembly.“ A Removal Order was issued by Sir Creasy for the arrest of the six leaders of the UGCC. They were held in the remote northern part of the Gold Coast following their arrests. A commission of enquiry chaired by Mr. Aiken Watson was set up to look into the riots. Other members of the Watson commission were Dr. Keith Murray, Mr. Andrew Dalgleish and Mr. E. G. Hanrott. Following their incarceration, the UGCC leaders collectively became national heroes known as the “Big Six”. Their popularity increased. On March 8, 1948 some teachers and students demonstrated against the detention of the Big Six. The demonstrators and were dismissed, and the national heroes were released:

The 1948 Accra-riots speeded the pace of political reform. Yet Dr. Nkrumah, always the radical, rejected proposals for a new Gold Coast constitution. In 1949, following a suspension and growing rift with Danquah and the UGCC leadership, Dr. Nkrumah resigned his position at UGCC and left to form his own Convention People’s Party (CPP). He proposed to precipitate a crisis through „positive action“: His followers took the cue and agitated for immediate self-government, leading to a state of emergency and Dr. Nkrumah’s detention once again by the British. But reform ensued, and the first national elections were held in 1951. The CPP triumphed, thanks to brilliant organization and to the symbol of its incarcerated leader. Although still under arrest, Dr. Nkrumah became the continent’s first African-born Prime Minister. On Feb. 12, 1951, he was released from prison and made „leader of government business.“ After winning the 1951 election, Dr. Nkrumah’s CPP went on to win subsequent elections in 1954 and 1956. His determination was: “Either I die, or I free my people!”

The Pre-Independence Aera

In the six years that elapsed between the first General Elections in 1951 and Ghana’s attainment of independence in 1957, the government of the CPP took bold initiatives to advance the development of the country economically, socially and politically. In the economic sphere, it launched a 5-year Development Plan for the country. Its achievements included the sealing of many of the country’s existing roads and the construction of new ones; the construction of a bridge over the Volta at Adomi, to facilitate travel between what is now the Volta Region and the rest of the country; the construction of a new and modern harbour at Tema; the extension of Huni valley to Kade railway line to Accra and Tema; support for the cocoa industry and formulation of plans for the building of a hydro-electricity plant at Akosombo. In the social field, the CPP Government launched in 1952 the free compulsory primary education programme for children aged between 6 and 12 years. It increased government expenditure on primary education from £207.500 in 1950-51 to over £900.000 in 1952. As a result, the number of registered pupils in elementary schools increased from 212.000 in 1950 to 270.000 in 1952. Sixteen new Teacher Training Colleges were established to increase the output of teachers while the number of government-assisted Secondary Schools increased from 13 in 1951 to 31 in 1955. In 1952, the CPP Government established the Kumasi College of Arts Science and Technology and co-operated with Nigeria, Gambia and Sierra Leone to establish the West African Examinations Council to organize and administer examinations in the four countries. University education was free and textbooks were supplied to all pupils in primary, middles and secondary schools. Politically, the CPP Government accelerated the pace of Africanisation of the civil and public service, resulting in the rise of the number of Africans in the so-called “European posts” from 171 in 1949 to 916 in 1954 and to 3.000 in 1957. It also introduced a new system of Local Government with an elected majority in 1952. But the biggest political challenge to the government during this period was the threat to the cohesion of the state. At midnight on March 6, 1957, the British Colony of Gold Coast was officially declared an independent nation. In a giddy ceremony, a crowd of 50.000 burst out: „Ghana is free!“

In his independence speech, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah proclaimed:

“Ghana our beloved country is free for forever. But the independence of Ghana would be meaningless if not linked up to the total liberation of Africa!”

His vision of Ghana as first president and the “Big Son of Mamma Africa” was to make his country a beacon of success in Africa and power the movement towards African nationalism as he had studied in racism in America between black and white. Therefore, he pulled a historical name “Ghana”. The Empire of Ghana which had existed about 400-1000 A.C., had been located in what is now South-eastern Mauritania, Western Mali, and Eastern Senegal. It was known to its own citizens, the Mande subgroup the Soninke, as Wagadou. The dou in the empire’s name is a Mandé term for „land“ and is prevalent in place names throughout central West Africa. The waga in the name roughly translates to „herd“. Thus, Wagadou translates to „Land of Herds“. The Empire became known in Europe and Arabia as the Ghana Empire by the title of it. Most of the early written information about the empire was coming from Andalusian traders who frequently visited the country, and from the Almoravids, who invaded the kingdom in the late 11th century. The first written mention of the kingdom comes soon after it was contacted by Sanhaja traders in the eighth century. In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, there are more detailed accounts of a centralized monarchy that dominated the states in the region. The Cordoban scholar al-Bakri collected stories from a number of travellers to the region, and gave a detailed description of the kingdom in 1067. At that time, it was alleged by contemporary writers that the Ghana could field an army of some 200.000 soldiers and cavalry. Earlier and later, there were more highly civilized kingdoms in North-West and West Africa like Nubien and Kusch (around 2800 B.C.- 400 A.C.), Mali and Timbuktu (around 1200 A.C.) and Simbabwe (from 1250 A.C. on) which earn our high respect and do not fit at all with the slave traders’ and Hitler’s philosophy of the “simple African bushmen” without brain and with only muscles. Dr. Kwame Nkrumah sought to improve conditions for the black Diaspora worldwide. „There was a conscious effort,“ says Kwamina Panford, chair of African-American studies at North-eastern University, „to link Ghanaian freedom with the freedom of all black people around the world”. Within 10 years of Ghanaian independence, 30 African nations were self-governing, and Dr. Nkrumah’s broader goal of continent-wide self-rule had been largely achieved.

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah together with Martin Luther King (1957) who was present at the independence celebration and later wrote about it, enthusiastically

Purpose

Dr. Nkrumah implemented an active foreign policy to bring Ghana from the periphery of world affairs to a more important role in the struggle for African liberation and unity. He was instrumental in the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), underwriting preliminary conferences on African unity and developing personal ties with other African leaders. Dr. Nkrumah was increasingly popular, but now faced the huge challenges of uniting a country of people that didn’t have that much in common. On the contrary, some groups still carried hostility towards each other from centuries of wars and the scars of slave trade. Political parties which were regional or tribal oriented were prohibited to enforce a feeling of national unity.

At the 8th July 1960, Ghana become a republic, and Dr. Nkrumah addressed an attentive parliament on a wide range of domestic and world affairs, including the possibility of Ghana leaving the Commonwealth if apartheid South Africa remained a member.

An animated Dr. Kwame Nkrumah delivering his historic speech at the OAU (Organization of African Unity) 1963 founding conference in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, said: „I am happy to be here in Addis Ababa on this most historic occasion. I bring with me the hopes and fraternal greetings of the government and people of Ghana. Our objective is ‘African Union Now’. There is no time to waste. We must unite now or perish. I am confident that by our concerned effort and determination, we shall lay here the foundations for a continental Union of African States. A whole continent has imposed a mandate upon us to lay the foundation of our union at this conference. It is our responsibility to execute this mandate by creating here and now, the formula upon which the requisite superstructure may be erected. On this continent, it has not taken us long to discover that the struggle against colonialism does not end with the attainment of national independence. Independence is only the prelude to a new and more involved struggle for the right to conduct our own economic and social affairs; to construct our society according to our aspirations, unhampered by crushing and humiliating neo-colonial controls and interference. From the start, we have been threatened with frustration where rapid change is imperative and with instability where sustained effort and ordered rule are indispensable. No sporadic act or pious resolution can resolve our present problems. Nothing will be of avail, except the united act of a united Africa.”

„Unite or sink“

Dr. Nkrumah continued: “…We have already reached the stage where we must unite or sink into that condition which has made Latin America the unwilling and distressed prey of imperialism after one-and-a-half centuries of political independence. As a continent, we have emerged into independence in a different age, with imperialism grown stronger, more ruthless and experienced, and more dangerous in its international associations. Our economic advancement demands the end of colonialist and neo-colonialist domination in Africa. But just as we understood that the shaping of our national destinies required of each of us our political independence and bent all our strength to its attainment, so we must recognise that our economic independence resides in our African union and requires the same concentration upon the political achievement. The unity of our continent, no less than our separate independence, will be delayed if, indeed, we do not lose it, by hobnobbing with colonialism. African unity is, above all, a political kingdom which can only be gained by political means. The social and economic development of Africa will come only within the political kingdom, not the other way round. Is it not unity alone that can weld us into an effective force, capable of creating our own progress and making our valuable contribution to world peace? Which independent African state, which of you here, will claim that its financial structure and banking institutions are fully harnessed to its national development? Which will claim that its material resources and human energies are available for its own aspirations? Which will disclaim a substantial measure of disappointment and disillusionment in its agricultural and urban development? In independent Africa, we are already re-experiencing the instability and frustration which existed under colonial rule. We are fast learning that political independence is not enough to rid us of the consequences of colonial rule. The movement of the masses of the people of Africa for freedom from that kind of rule was not only a revolt against the conditions which it imposed. Our people supported us in our fight for independence because they believed that African governments could cure the ills of the past in a way which could never be accomplished under colonial rule.”

August 27th 1963: William Edward Burghardt Du Bois dies in Accra. The African-American W.E.B. Du Bois was born as in Massachusetts (1868) and became one of the most important contributors to the Pan-African movement, which again influenced Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and the history of Ghana. Du Bois was invited by Dr. Nkrumah to settle in Ghana after independence.

The End

February 24th, 1966: A military coup (without blood-shed) ended the rule of Dr. Nkrumah and his government. The coup was made by British-trained officers and took place while Dr. Nkrumah was paying an official visit to chairman Mao in Beijing. He sought asylum at his personal friend President Sékou Touré in Guinea. In the following days and weeks all Dr. Nkrumah statues in Accra were taken down by the crowds…

The paradox of poverty in the midst of plenty even today

Dr. Nkrumah said: “For centuries, Europeans dominated the African continent. The white man arrogated to himself the right to rule and to be obeyed by the non-white; his mission, he claimed, was to ‘civilize’ Africa. Under this cloak, the Europeans robbed the continent of vast riches and inflicted unimaginable suffering on the African people. All this makes a sad story, but now we must be prepared to bury the past with its unpleasant memories and look to the future. All we ask of the former colonial powers is their goodwill and cooperation to remedy past mistakes and injustices and to grant independence to the colonies in Africa…. It is clear that we must find an African solution to our problems, and that this can only be found in African unity. Divided we are weak; united, Africa could become one of the greatest forces for good in the world. Although most Africans are poor, our continent is potentially extremely rich. Our mineral resources, which are being exploited with foreign capital only to enrich foreign investors, range from gold and diamonds to uranium and petroleum. Our forests contain some of the finest woods to be grown any where. Our cash crops include cocoa, coffee, rubber, tobacco and cotton. As for power, which is an important factor in any economic development, Africa contains over 40% of the potential water power of the world, as compared with about 10% in Europe and 13% in North America. Yet so far, less than 1% has been developed. This is one of the reasons why we have in Africa the paradox of poverty in the midst of plenty, and scarcity in the midst of abundance. Never before have a people had within their grasp so great an opportunity for developing a continent endowed with so much wealth. The economic development of the continent must be planned and pursued as a whole… Critics of African unity often refer to the wide differences in culture, language and ideas in various parts of Africa. This is true, but the essential fact remains that we are all Africans, and have a common interest in the independence of Africa. The difficulties presented by questions of language, culture and different political systems are not insuperable. If the need for political union is agreed by us all, then the will to create it is born; and where there’s a will there’s a way. The present leaders of Africa have already shown a remarkable willingness to consult and seek advice among them. Africans have, indeed, begun to think continentally. They realise that they have much in common, both in their past history, in their present problems and in their future hopes. To suggest that the time is not yet ripe for considering a political union of Africa is to evade the facts and ignore realities in Africa today. The greatest contribution that Africa can make to the peace of the world is to avoid all the dangers inherent in disunity, by creating a political union which will also by its success, stand as an example to a divided world. A Union of African states will project more effectively the African personality. It will command respect from a world that has regard only for size and influence. The scant attention paid to African opposition to the French atomic tests in the Sahara, and the ignominious spectacle of the U.N. in the Congo quibbling about constitutional niceties while the Republic was tottering into anarchy, are evidence of the callous disregard of African Independence by the Great Powers. We have to prove that greatness is not to be measured in stockpiles of atom bombs. I believe strongly and sincerely that with the deep-rooted wisdom and dignity, the innate respect for human lives, the intense humanity that is our heritage, the African race, united under one federal government, will emerge not as just another world bloc to flaunt its wealth and strength, but as a Great Power whose greatness is indestructible because it is built not on fear, envy and suspicion, nor won at the expense of others, but founded on hope, trust, friendship and directed to the good of all mankind. The emergence of such a mighty stabilising force in this strife-worn world should be regarded not as the shadowy dream of a visionary, but as a practical proposition, which the peoples of Africa can, and should, translate into reality. There is a tide in the affairs of every people when the moment strikes for political action. Such was the moment in the history of the United States of America when the Founding Fathers saw beyond the petty wrangling of the separate states and created a Union. This is our chance. We must act now. Tomorrow may be too late and the opportunity will have passed, and with it the hope of free Africa’s survival.”

For more information, contact the “African School of Thoughts”

in the Akebulan- Global Mission e.V.:

info@akebulan-gm.org; www.akebulan-gm.org

Räuschstr. 37, 13509 Berlin (Borsigwalde)

Tel.: 030/ 772 17 79 (Pastor Peter Arthur)