The Preventive Detention Act led to widespread disaffection with Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s administration. Some of his men used the law to have innocent people arrested so that they could acquire their political offices and business assets. Advisers close to Dr. Kwame Nkrumah became reluctant to discuss Ghana’s true situation for fear that they might be seen as being critical. When the nation’s clinics ran out of pharmaceuticals, no one notified him. Some people believed he no longer cared, the advisers trembled, and the police came to resent their role in society. Meanwhile, a quite justifiable fear of assassination meant Dr. Kwame Nkrumah became less accessible. Ghana was declared a one-party state with Dr. Kwame Nkrumah as Life President in 1964.

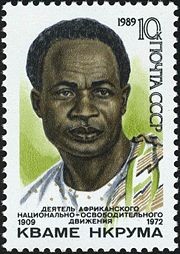

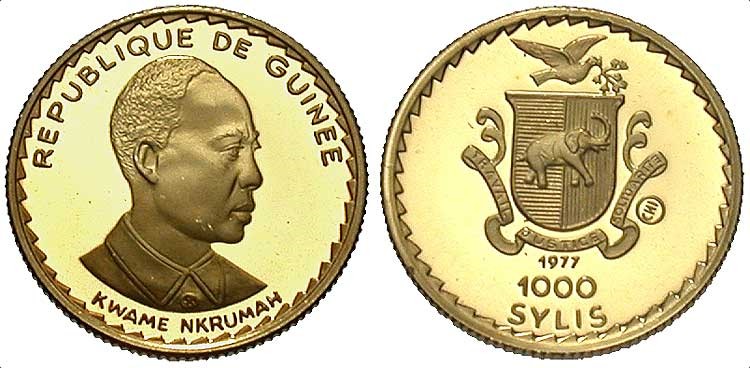

Today, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah is still one of the most respected leaders in African history. In 2000, he was voted Africa’s Man of the Millennium by listeners of the BBC World Service. In order to strengthen the continent of Africa and to make it less vulnerable to outside influence, President Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana strongly believed that the continent should be united. Thus, in the late 1950s, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah started a movement which stressed the immediate unity of the African continent.

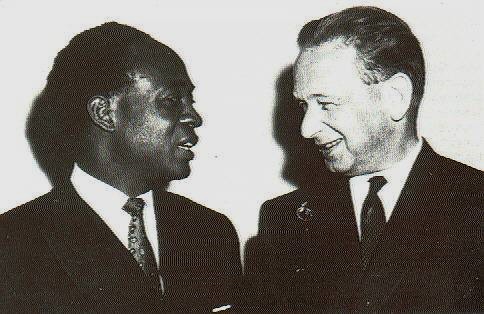

This picture was taken in 1959, when the three leaders met in Sanniquellie, Nimba County, Liberia, to discuss African unity and solidarity

When Dr. Kwame Nkrumah introduced the concept of African Unity to the continent, a division which was based on the implementation of this new concept, was created at the onset. On the one hand, there were those countries which believed in the immediate unity of Africa. These countries were originally Ghana, Guinea, and Mali. Later on Egypt, the Transitional Government of Algeria, and Morocco, joined the Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union to form the Casablanca Group. On the other hand, the twenty-four member Monrovia Group, otherwise known as the Conservatives, which included Nigeria, Liberia, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Togo, and many others believed in a much more gradual approach to the question of African unity. Many believed that the rift between the two groups would become permanent and thus ending the hopes and dreams of African Unity.

who was one of the leading members of the Monrovia Group

In Lagos, Nigeria, the core members of the Monrovia Group started to attack the Casablanca Group. Speakers like Azikiwe of Nigeria would condemn the rival group on various issues, including its failure to condemn interference in the internal affairs of member states. In his speech, Governor-General Azikiwe publicly acknowledged the obvious split between his group and the Casablanca Block. It was during this historic moment that the Ethiopian Foreign Minister began to lobby the conference participants in the hopes of having the next Monrovia meeting in the Ethiopian capital. Ketema Yifru, who was on a mission to bring these two groups together, believed that once he had the approval of the Monrovia Powers, he would work on having the Casablanca members attend the proposed Addis Ababa Summit Conference. The relentless effort of Foreign Minister Ketema Yifru paid off: All the Monrovia Summit participants accepted Ketema Yifru’s proposal of having the next Monrovia meeting in Addis. Therefore in May 1963, these two opposing groups were able to come together to form the Organization of African Unity.

Since Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s official election as the greatest African of all time in the year 2007 as well as the globally reported Golden Anniversary celebrations, many Ghanaians, whenever we encounter other Africans on the continent or in the Diaspora, feel increasingly under pressure to admit to guilt over the overthrow of Dr. Nkrumah. The impression has been created that Dr. Nkrumah’s travails reflect the biblical saying: “A prophet has no honour in his own country’’ (Luke 4, 24). We Ghanaians, according to this view, rejected Dr. Nkrumah’s ministry while the rest of Africa, and eventually the world, recognised his genius and hailed him as a visionary and seer. The recent outpouring of affection, admittedly posthumous but touching all the same, has been interpreted as a deliberate or subconscious attempt to atone for our sins and make amends, even though the general consensus is that we still have a long way to go.

When Dr. Nkrumah’s government was overthrown in his absence, he found himself stranded in Beijing, virtually homeless. What is worse, the Chinese had cancelled the rest of his peace-building mission, and were keeping him strictly quarantined from all the other guests, for to their oriental sensitivity he had become an embarrassment. His ideological comrade Sekou Toure of Guinea promptly extended a warm invitation to Dr. Nkrumah and upon the latter’s arrival in Conakry even made him co-president for a brief time. Sekou Toure was of course, together with Modibo Keita and Dr. Nkrumah, a member of the ideological triumvirate that through such programs as the Ghana-Guinea-Mali union strove to forcefully promote a federalist plan for Africa. Sekou Toure’s action appears as an indictment on Ghana’s national conscience when viewed broadly. But as the memoirs of those closest to Dr. Kwame Nkrumah such as June Milne and Erica Fowell have revealed, it is not as rosy as all that. For Sekou Toure was a slightly paranoid sort of person. Yes he did shelter Dr. Nkrumah in a villa, Syli house, but he forbade casual contact between his guest and his country folk with the sad result that the villa literally went to pieces around the great deposed president. The water soon stopped flowing, but plumbers weren’t allowed in, and then the lights went out, too. The furniture was in tatters and the paintwork simply putrid by the time when Dr. Nkrumah’s gilded captivity ended. Despite Dr. Nkrumah’s failing health Toure wouldn’t consent to his being flown out of the country. He insisted that Guinean doctors could do the job even though it was painfully obvious that the only job they were doing was shooting their patient full of ineffective medication. There is even evidence to suggest that the treatment was actually worsening his health. His family was not allowed to visit, and since he wasn’t permitted to leave the country either one can only imagine the psychological torment the man must have undergone! When finally Toure gave his consent and relaxed the surveillance which he had encased around his friend so Dr. Nkrumah could travel, it was to Socialist Romania that he was sent. But even there Toure ensured that he had only the barest minimum of material support. No wonder he never recovered from whatever illed him. Every indication is that the Guinean strongman did not trust his Ghanaian comrade. Both were intellectual colossuses of the African socialism tradition and were certainly brothers-in-arms as far as ideology went, but trust seemed somewhat beyond the relationship. The trust and suspicion issue is interesting as they seem to have underlayed the reception of Dr. Nkrumah and his Pan-Africanist ideology across the African continent. The louder he was hailed the deeper mistrust and suspicion of him grew. Of all the African revolutionaries who learnt at his feet or by his side, only Mugabe and Uganda’s Obote seemed to have been immune.

Alhaji Sir Taffawa Balewa, Nigeria’s post-independence leader described Dr. Nkrumah’s conduct of foreign relations from Accra as “the madness in Ghana”. He was merely echoing the disaffection the Nigerian political elite felt about the state of affairs in Ghana dating back to Nnamdi Azikiwe’s famous bust-up with Dr. Kwame Nkrumah over the federalist confederacies argument when both men were pan-African student activists in London in the late 40s. Azikiwe was a co-federalist, which will these days probably make him a “regionalist”. He wanted Africa to unite step by step through intermediate blocs. So he proposed a union of English-speaking countries in West Africa after independence. Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of course did not want to have anyone of these. We all know the speech: “Ethiopia will stretch forth its hand… Africa must unite!” He wanted a federal project or nothing; common unity for all Africa’s peoples regardless of colonial-imposed differences including language.

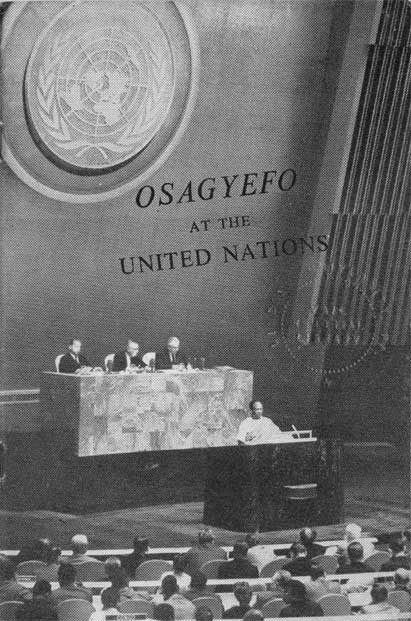

This stance coupled with his emphasis on political unity instead of economic cooperation generated much suspicion of Dr. Nkrumah’s motives across Africa. When the Congolese crisis flared up in the sixties, the opportunity appeared for criticism of Dr. Nkrumah’s doctrine to increase. Dr. Nkrumah, alongside his Afro-Arab allies in the Casablanca grouping, backed the pro-Lumumba rebels under Gizenga against Moise Tshombe the de facto ruler of Congo. 13 former French colonies promptly banded together in Nouakchott to undermine the Ghanaian position. They accused Dr. Nkrumah of sponsoring terrorism and even of harbouring expansionary ambitions. Togo’s Olympic in 1965, foaming at the mouth, condemned Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s alleged annexation plan for his country and was joined in the chorus of denunciation by both Benin and the Ivory Coast. They also criticised Dr. Nkrumah because he was exhibiting a band of guerrillas who had been trained in one of his jungle warfare schools. Latter political historians have tended to dismiss this acrimony as simply part of the neo-colonial resistance in the face of African Socialism’s march, and as such nothing to do with the particular merits of Dr. Nkrumah’s doctrine of African unity. The facts however are, that even ideological comrades such as Nyerere from Tanzania viewed Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s dogmatic approach very unfavourably indeed. Nyerere’s counter-reaction to Dr. Nkrumah’s earnest disapproval of the former co-federalist plan for East Africa bordered on contempt. He raised his voice against Dr. Nkrumah’s title “Osagyefo” (Messiah) which the people had given him. He described Dr. Nkrumah publicly as motivated solely by base motives of personal grandeur. To rub it in, he called Dr. Kwame Nkrumah “petty” and “mischievous”.

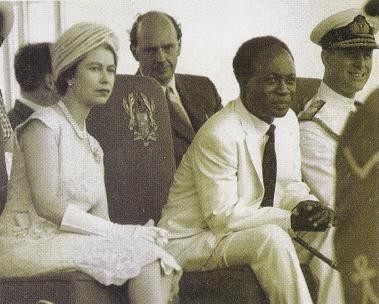

Everywhere he turned Dr. Kwame Nkrumah appeared to be under pressure. Regarding his tactical genius, it is impossible to see how he could have achieved any of his non- African foreign policy objectives. He effectively had to blackmail the British Prime Minister by threatening to cancel a visit by the Queen to get the former to persuade the USA to fund the Akosombo dam. Torn between Soviet and Western interests, as a consequence of his Non-Aligned doctrine, which meant that the West considered Dr. Nkrumah a dangerous communist while the UdSSR and China could never fully trust him, he was reduced to double-minded diplomacy. The Sovjet Union was assisting him expand his presidential guard with a view to creating a third counterweight to the National Army and Police Service, but was at the same time at odds with him over Rhodesia which later became Zimbabwe and various aspects of the Congo question. America was bankrolling Dr. Nkrumah’s dam and at the same time questioning his underground political support of Southern Africa. It is not surprising that the negotiations of the Akosombo hydroelectric project’s financing agreement were described by Yergin and Stanislaw as the most complex legal chess game in history. In fact, that complexity has only recently been resolved with the closing down of Valco. It were foreign campaigns, surrounded in equal measure by glory and mistrust, that in the end undid Dr. Nkrumah.

The history of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s experiences in Africa and elsewhere is altogether one of unanswered love. Sometimes, his political brilliance and tactical genius notwithstanding, Dr. Nkrumah was idealistic to the point of self- harm. Ghanaians certainly dealt him a raw deal when we sent him to exile and set about methodically unraveling his legacy, but we took part in singing a continental chorus about the suicidal implications of Dr. Nkrumah’s doctrinal line.

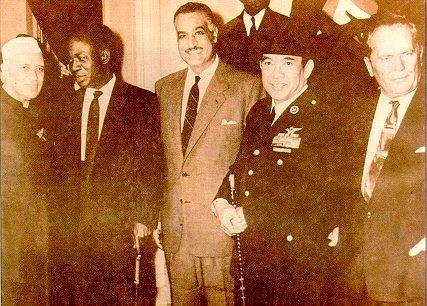

Date: December 1958 Country: Ghana Credit: Unknown Holder: Private collection of George M. Houser

1958 Philadelphia visit

University of Pennsylvania Archives

Alumni Records Collection

Africanism and Culture

given at the

Congress of Africanists, Accra, Ghana, December, 1962)

In a speech to the National Assembly on 1 February 1966, 23 days before he was overthrown, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah warned with great alarm: “A one-party system of government is an effective and safe instrument only when it operates in a socialist society!”

In class struggle in Africa, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah wrote: “Every form of political power, whether parliamentary, multi-party, one-party, or an open military dictatorship, reflects the interest of a certain class or classes in society. In a socialist state, the government represents the workers and peasants. In a capitalist state, the government represents the exploitative class. The state then, is the expression of the domination of one class over other classes‘. Yet through subversion, lies, corruption, the IMF, World Bank, and CIA pressures, the enemies of African progress and political unification have influenced most African politicians and intellectuals by prescribing the multi-party system as the only form of political governance. Even though the effects of multi-party system have been disastrous everywhere in the developing world, any leader with a vision of an alternative form of governance would be overthrown by the CIA. This is what happened to Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and what presently almost happened to Mugabe in Zimbabwe.

If we have lost touch with what our forefathers discovered and knew, this has been due to the system of education to which we were introduced. This system of education prepared us for a subservient role to Europe… It was directed at estranging us from our own cultures in order the more effectively to serve a new and alien interest.

The central myth in the mythology surrounding Africa is that of the denial that we are a historical people. It is said that whereas other continents have shaped history and determined its course, Africa has stood still, held down by inertia. Africa, it is said, entered history only as a result of European contact. Its history, therefore, is widely felt to be an extension of European history. Hegel’s authority was lent to this a-historical hypothesis concerning Africa. And apologists of colonialism and imperialism lost little time in seizing upon it and writing wildly about it to their heart’s content.

To those who say that there is no documentary source for that period of African history which pre-dates the European contact, modern research has a crushing answer. We know that we were not without a tradition of historiography, and, that this is so is now the verdict of true Africanists. In the 4th century, the King of Ghana ruled over a complex society with a street system, written laws and an army with over 200.000 soldiers. Around 1200, this kingdom was overtaken by the Mali-kingdom whose capital Timbuktu developed into a centre of trade and science. African historians, by the end of the 15th century, had a tradition of recorded history and certainly by the time when Mohamud al-Kati wrote Tarikh al-Fattash. This tradition was incidentally much, much wider than that of the Timbuktu school of historians. In Zimbabwe, there existed also an early high culture with a big capital.

The Chinese, too, during the T’ang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), published their earliest major records of Africa. In the 18th century, scholarship connected Egypt with China; but Chinese acquaintance with Africa was not only confined to knowledge of Egypt. They had detailed knowledge of Somaliland, Madagascar and Zanzibar and made extensive visits to other parts of Africa.

Between ancient times and the 16th century, some European scholars forgot what their predecessors in African Studies had known. This amnesia, this regrettable loss of interest in the power of the African mind, deepened with growth of interest in the economic exploitation of Africa.

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana- a clear leftist who Kennedy had backed against heavy odds and who was perhaps the greatest of that period’s African leaders- was overcome with sadness upon hearing of the young American president’s death. In a speech at that time, he told his citizens that Africa would forever remember Kennedy’s great sensitivity to that continent’s special problems (Mahoney, p. 235).

Haile Selassie from Ethiopia

Will Africa Ever Unite?

“As far as I am concerned, I am in the knowledge that death can never extinguish the torch which I have lit in Ghana and Africa, long after I am dead and gone the light will continue to burn and be borne aloft giving guidance to all people” (Dr. Kwame Nkrumah)

In all my researches for my second speech about Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, I want to end up saying that this special man has also visited Berlin once in his life. He came to the Humboldt University in 1962, and because of this visit we find the Ghana-Street in Wedding, today.

All I can say about him as a Ghanaian, is: Dr. Nkrumah was a “people’s person”. May God bless Ghana and the world with selfless people like him!

From Pastor Peter Arthur

More information at “African School of Thoughts”

in Akebulan- Global Mission e.V.:

info@akebulan-gm.org; www.akebulan-gm.org

Räuschstr. 37, 13509 Berlin (Borsigwalde)

Information Sources:

– Ghana (Gluth/ Seidel: VEB Brockhaus Vlg Leipzig 1962)

– „Der große Atlas der Weltgeschichte“, Copyright Parragon Books Ltd.

– Website „Ethiopia“

– Website „Ghana“